This article was written by Verena Saischek in the context of the class „rethinking Economy“ at the university and published with her permission.

Introduction

The solution I would like to discuss in this assignment brings us deep into the fields of environmentalism, saving the world’s ecosystems and into the field of law. I am going to summarize the worldwide ongoing “Rights of Nature” movement, which intends to revolutionize the jurisdiction systems, granting basic rights to nature or even personhood status, so that before the court, nature can have a legal standing and can fight for itself.

History of Origins

As Hope Babcock (2016) states in her article, the Rights of Nature movement had its origins in the year 1972 with an article published by law professor Christopher Stone, which was titled “Should trees have standing – toward legal rights for natural objects”.

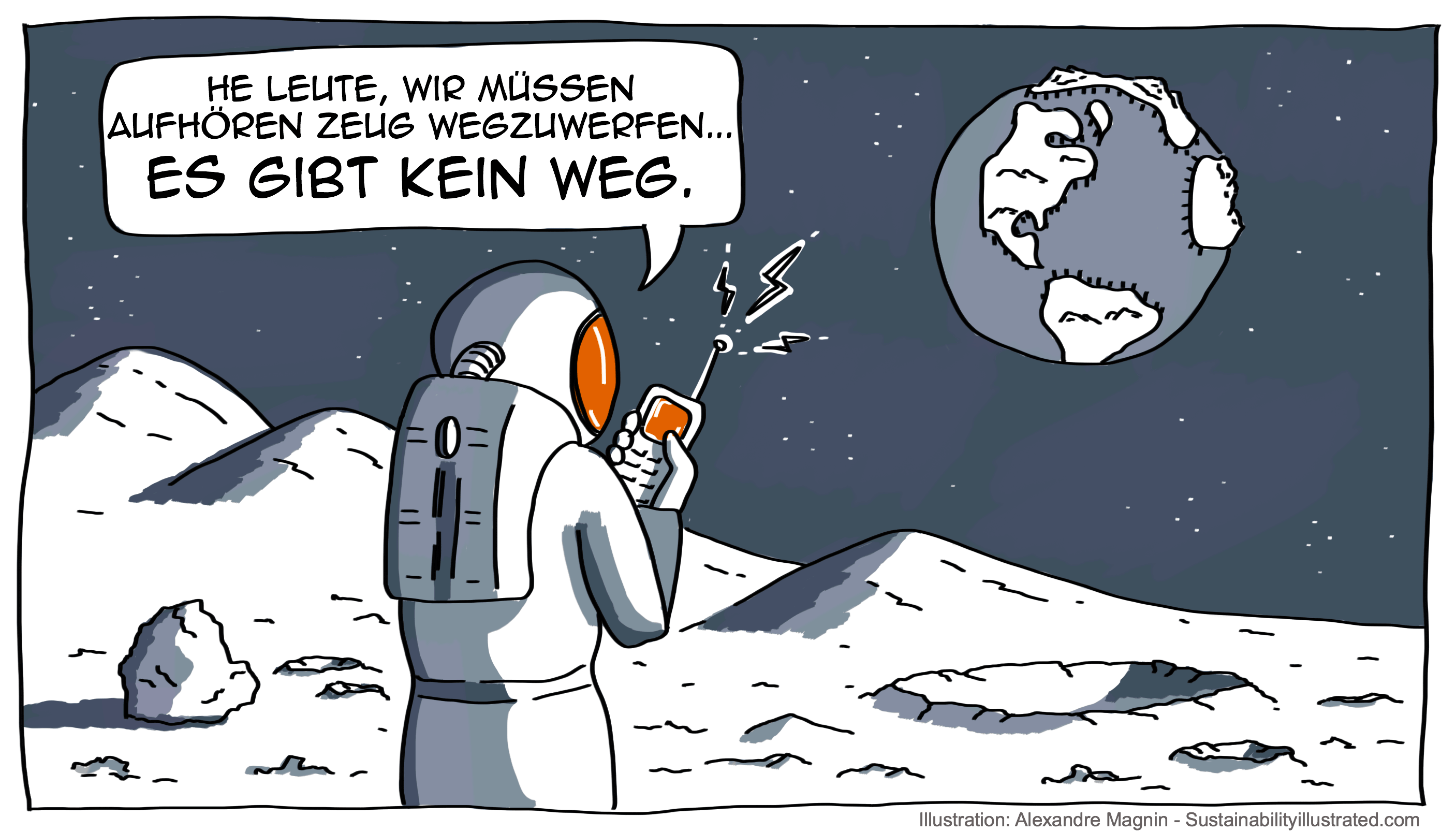

Stone described the problem, that under the existing law system, nature does not have rights to defend its own interests. This is due to the legislation, in the United States stated in Article III. In a lawsuit, there needs to be a direct, nonhypothetical personal injury. If there is harm to nature, this harm will only be considered in front of a court, if the harm also affects humans. So if a plaintiff cannot prove a cause-effect relationship between himself, a threatened resource and an accused party, there is no case.

This makes it almost impossible for environmental organizations to use the courts to protect nature (Babcock, 2016).

The fundamental conflict can be revealed in the opposing worldviews of anthropocentrism and ecocentrism. In our Western anthropocentric worldview, humans consider themselves in the center, while nature and animals are treated as objects. They only have instrumental value for human use, but not an intrinsic value. In contrast there is the ecocentric and holistic worldview, which can be found in Buddhism or within indigenous cultures, that have a much stronger connection with nature. They believe that humans are only a part in a much wider organism (Villavicencio Calzadilla & Kotzé, 2018).

Since our law system is clearly anthropocentric, it does not protect nature against harm and it even increases environmental destruction. So Christopher Stone proposed the reformation of the justice system, so that nature should get rights and consequently a legal standing in court. If nature is a rights holder, then humanity has responsibilities. With his article Stone hoped to influence lawyers and judges – and he did! Babcock quotes a justice named Blackmun, who reacted to Christopher Stone’s ideas and saw the legal recognition of environmental rights as much more than a way for saving national forests. “It was a means through which environmentalism could evolve into an integral element of the ills addressed by law, permeating the federal constitution, laissez faire economics, nonpartisan politics, and even our cultural sense of morality” (Justice Blackmun, as cited in Babcock, 2016, p.19). So changing our justice system and granting nature rights could also have a crucial symbolic effect on society.

Although Stone’s theory had an impact, it took decades for lawyers to turn theory into reality. Finally, from the first decade of the 21st century onwards, more and more cases not just in the United States but all around the world popped up, where rights of nature were considered in court rooms and legislatives were being changed to include a certain legal status for the environment.

Milestones and examples

In 2006, Tamaqua Borough in Pennsylvania was the first US community to recognize the rights of nature in a state court lawsuit brought by Pennsylvania General Energy against the township. A citizen environmental group as well as lawyers represented the Little Mahoning Creek and its right to protection. As a consequence, a law was enacted by the town banning the drilling of oil and gas wastewater wells (Babcock, 2016). Since then, dozens of communities and grassroots movements in Colorado, Columbia and other states have been taking similar measures.

Indigenous communities play an important role in fighting for the rights of nature. This has also been the case in Ecuador and Bolivia. In 2008, after an approving vote of the country’s population, Ecuador became the first country in the world to recognize the Rights of Nature in its national constitution. As Kotzé and Calzadilla (2017) quote article 71 of the new constitution:

Nature, or Pacha Mama, where life is reproduced and occurs, has the right to integral respect for its existence and for the maintenance and regeneration of its life cycles, structure, functions and evolutionary processes. All persons, communities, peoples and nations can call upon public authorities to enforce the rights of nature […]. (p. 22).

The first successful lawsuit featured the Vilcabamba River as the plaintiff, represented by an American couple who sued the provincial government in matters of a planned highway, that would interfere with and pollute the river. As another successful consequence, the Chevron-Texaco corporation was fined 9.5 billion dollars for damages to the Amazon rainforest, although the sanction has yet to be enforced (Cailloce, 2017).

In 2010 and 2012, Bolivia adopted two Laws of the Rights of Mother Earth. Like in the case of Ecuador, the large indigenous community initiated this change with the support of president Evo Morales, who then created and hosted the World People’s Conference on Climate Change and the Rights of Mother Earth in Bolivia, which resulted in the Universal Declaration on the Rights of Mother Earth. As a further consequence, the UN General Assembly proclaimed the 22nd of April to be “International Mother Earth Day”.

More recently, a different approach to the Rights of Nature has been applied in New Zealand, India and Australia, where individual natural features, mostly rivers, have been granted legal personhood status by national governments for their own protection. In New Zealand, this is the case with the Whanganui River and the national park Te Urewera, which both are treated from 2014 onwards as “legal entities with all the rights, powers, duties, and liabilities of a legal person” (New Zealand Legislation, n.d.). Here too, the indigenous community was the initiator behind these developments. Guardians, consisting of government and Maori representatives, were assigned to act for the rights of the new legal entities. In 2017, the High Court of Uttarakhand in India granted the Ganges and Yamuna rivers legal personhood status. This ruling could be a crucial step in the combat against pollution caused by industrial waste and sewage systems (Cailloce, 2017).

In addition to constitutional changes and to local campaigns for the promotion of these changes in further countries like Nepal, Sweden, England, Scotland or Mexico, certain international developments can also be mentioned. A Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature was formed, which since 2014 organizes international gatherings of experts, scientists and citizens, titled Rights of Nature Tribunals. “This ‘People’s Tribunal’“, which has already been taking place in Ecuador, Peru, France and Germany, “provides a vehicle for reframing and adjudicating prominent environmental and social justice cases within the context of a Rights of Nature based earth jurisprudence” (Global Alliance for Rights of Nature, n.d.). It has no binding consequences, but recommends actions for restoration, mitigation and prevention and provides a framework for educating the public, raising awareness and advising governments. The tribunals also provide solid arguments for future legal action against multinational corporations. Cases like Climate Change, the Great Barrier Reef or Fracking are only a few examples that have already been discussed.

A last crucial example shall be mentioned. As Cailloce (2017) states, in 2015, the Urgenda group along with 800 Dutch citizens took the government of the Netherlands to court. They accused the State of being negligent and not taking sufficient action against climate change. Urgenda won and the government was ordered to review its greenhouse gas emissions commitments. This unprecedented case shows the potential of the Rights of Nature movement, since in the future it might be possible for citizens to sue their governments for not taking their role in protecting the environment and therefore protecting future generations seriously enough.

Problems and Controversies

What sounds very good in theory, unfortunately has quite some implementation problems in reality. The Rights of Nature laws in Ecuador and Bolivia can best illustrate this. Although the laws do exist, civil society groups have struggled to enforce the rights of nature. In both countries, environmental protection stands in conflict with the economy of a developing country, depending on the very nature-damaging activities that these countries would like to prevent. For Bolivia’s president Evo Morales, the elimination of poverty is the national priority, but instead of pursuing this goal with ecologically sustainable means, he even promotes the exploitation of natural resources via the extractive industry, causing ongoing and irreversible destruction of nature and indigenous land, while to the international world acting the role of „Hero of Mother Earth“ (as cited in Villavicencio Calzadilla & Kotzé, 2018, p. 19).

Babcock (2016) points out that rights always exist in competition with other rights. Therefore it might be possible that in regard to a specific harm to nature, opposing agendas within a community or state stand in conflict. Who, then, gets to decide on behalf of nature’s rights? The author also discusses several problems, both institutional and practical concerns, in the implementation of Rights of Nature in the jurisdiction, but nevertheless points out, that most of them might be easily solvable. One main concern is the risk of flooding the courts with numerous smaller lawsuits and intruding into the sphere of political decision-making. This could be solved by limiting the type of cases brought by nature to those that involve substantial importance, irreplaceable resources or irreparable injury, caused or threatened by government inaction. Yet the question remains how to define an irreparable injury. Another problem is based on the question of who should speak for nature in court. Christopher Stone suggested assigning guardians, which is already the case in New Zealand and India, as discussed above. Babcock proposes the alternative of using qualified lawyers, who possess the commitment and expertise. An interesting concern rises with the question, that if nature is granted rights, should it not also be granted responsibilities and in consequence made responsible for the harms it causes like floods or droughts? Stone actually agreed and proposed that judgements against nature could be paid from trust funds. However, Babcock thinks this approach would be a mistake. Also, who can be made responsible for a certain injury to nature, like the extinction of a species? One last question, also raised by Stone, is the matter of calculating the appropriate penalty for injuries to nature, although there already exist certain helpful laws like the Oil Pollution Act.

Some articles argue, that New Zealand’s narrower approach by granting individual

rivers or forests a legal personality status and guardians, may prove more effective in

the long run (Tanasescu, 2017).

Conclusion

In a lot of articles the Rights of Nature movement is discussed as a crucial way to protect our disappearing natural resources against economy’s strategies of exploitation. Theory and reality are still rooted very far apart, but the few game-changing cases in Ecuador, Bolivia, New Zealand or India are a clear proof for an ongoing snowball effect, that is swapping all over the world. Cultures and laws are providing a powerful new approach to protecting the planet. Rights of Nature constitutes a fruitful alternative to our existing systems of governance, capitalism, anthropocentrism and jurisdiction (Rawson & Mansfield, 2018). As Cailloce (2017) puts it, “the ‘greening’ of regional human rights courts—the European Court of Human Rights, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, and the relatively young African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights”, is already happening. And this is definitely a big step in the right direction.

Bibliography

Babcock, H. M. (2016). A Brook with Legal Rights: The Rights of Nature in Court. Ecology Law Quarterly, 43(1), 1–51.

Cailloce, L. (2017). Can the Law Save Nature? Retrieved from https://news.cnrs.fr/articles/can-the-law-save-nature, 22.12.2018.

Global Alliance for Rights of Nature. (n.d.). What is an international Rights of Nature

Tribunal? Retrieved from http://therightsofnature.org/rights-of-nature-tribunal/,

22.12.2018.

Kotzé, L. J., & Villavicencio Calzadilla, P. (2017). Somewhere between Rhetoric and

Reality: Environmental Constitutionalism and the Rights of Nature in Ecuador. Transnational Environmental Law, 6(03), 401–433. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2047102517000061

New Zealand Legislation. (n.d.). Te Urewera Act 2014. Retrieved from

http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2014/0051/latest/DLM6183601.html

, 22.12.2018

Rawson, A., & Mansfield, B. (2018). Producing juridical knowledge: “Rights of

Nature” or the naturalization of rights? Environment and Planning E: Nature

and Space, 0(0),1-21. https://doi.org/10.1177/2514848618763807.

Tanasescu, M. (2017). When a river is a person: from Ecuador to New Zealand,

nature gets its day in court. Retrieved from http://theconversation.com/whena-

river-is-a-person-from-ecuador-to-new-zealand-nature-gets-its-day-in-court-

79278, 22.12.2018

Villavicencio Calzadilla, P., & Kotzé, L. J. (2018). Living in Harmony with Nature?

A Critical Appraisal of the Rights of Mother Earth in Bolivia. Transnational

Environmental Law, 7(3), 397–424. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2047102518000201

This article was written by Verena Saischek in context of my lecture rethinking economy: globalization and consumer patterns at the University of Applied Sciences in Kufstein.

Picture used with friendly permission from https://www.pinterest.at/pin/36521446948780824/ (1000Petals.wordpress.com)[:]